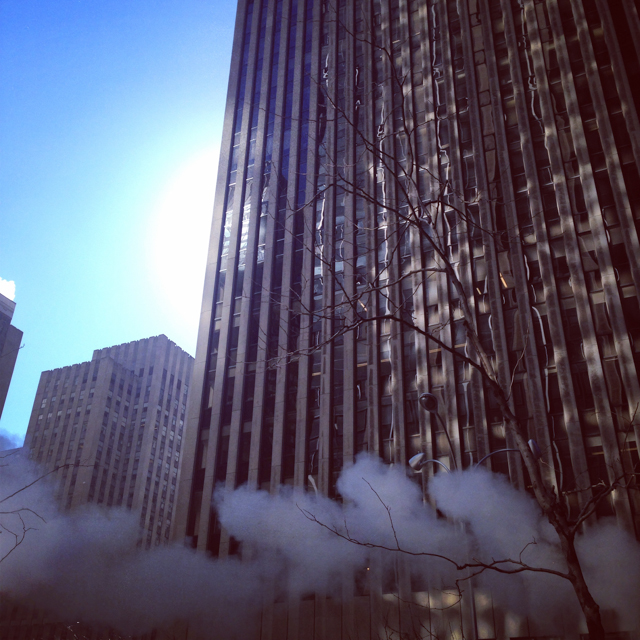

Steam City

Posted on May 18, 2014

So I posted an incident on facebook the other day, I was walking on 9th Avenue a woman with a British accent said to her friend “Why does steam come out of the sewers here it’s so disgusting.” I turned around and explained we have a steam system with underground pipes that Con Ed pumps into some buildings and sometimes you can see it come out of the top.

It never occurred to me that someone would not know about the steam system, but then I realized it’s unusual. I’m just from here and simply used to it as a part of the infrastructure. Even for New Yorkers it can be mysterious and easily forgotten, still it sometimes escapes out into the street, and you remember it’s there. It’s not quite like turning on a light, so you don’t notice it. I don’t even know if the building I work in uses it, though there are steam vents right outside. It of course doesn’t feel very modern, but it’s an amazing system and I have been poking around on Con Edison and wikipedia, most other articles on the internet seem to be using these two as sources.

From ConEd

“...New York Steam’s first central steam boiler plant, located at Cortlandt, Dey, Greenwich, and Washington Streets, was completed in 1881 and included 48 boilers and a 225-foot chimney — at the time, it was one of the tallest features of the lower New York skyline, second only to the spire of Trinity Church. The district steam installation was so novel it was the cover story of the November 19, 1881 issue of Scientific American.

On March 3, 1882, the company supplied steam to its first customer, the United Bank Building at 88-92 Broadway, on the corner of Wall Street. By December 1882, New York Steam boasted 62 customers. By 1886, the firm had 350 customers and five miles of mains, and began an expansion uptown. The system proved its reliability by operating throughout the deadly blizzard of March 11-14, 1888. Through the years, the company expanded and made numerous improvements in the design of steam meters, controls, insulation, and even the pipes themselves.

The company built by Wallace Andrews was to go on to even greater success during the 20th century, but he was not to see it. During the night of April 7, 1899, Andrews and much of his family perished in a house fire. His brother-in-law, G.C. St. John, who was out of town when the tragic fire occurred, was made president of the company and guided it for more than a decade during a prolonged legal battle over Andrews’ will.

The paralyzing effects of the litigation made necessary a financial reorganization that lasted from 1918 to 1921, but ultimately left the company, now called the New York Steam Corporation, prepared for a new era of expansion. By 1932, the tremendous Kips Bay Station (occupying the entire block along the East River between 35th and 36th Streets) and five other stations provided steam to more than 2,500 buildings. Among them were some of New York’s most famous landmarks: Grand Central Terminal, the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, the Daily News Building, Tudor City, Pennsylvania Station and Hotel, and Rockefeller Center. Just about every new skyscraper was a testament to the efficiency and reliability of steam service: most were built without smokestacks or individual heating plants.

During the 1930s, the New York Steam Company maintained mutually beneficial business arrangements that would be a portent of its eventual consolidation. The company supplied steam to the Consolidated Gas Company and its affiliated gas and electric companies in Manhattan. In turn, The New York Edison Company supplied steam from its Waterside and Fourteenth Street electric generating stations during the morning hours on cold days to help meet peak energy needs. In 1932, Consolidated Gas acquired approximately 75 percent of New York Steam’s common stock, and on March 8, 1954, the New York Steam Company fully merged with Consolidated Edison.

Today, Con Edison operates the largest district steam system in the United States. The system contains 105 miles of mains and service pipes, providing steam for heating, hot water, and air conditioning to approximately 1,800 customers in Manhattan.”

Steam can be co generated at the same time as electricity so it’s considered more green than some other types of heat. But yet, the central steam system only serves a portion of Manhattan, none of the boroughs and probably has seen the end of it’s expansion. We’ve also had a few steam pipe explosions in my memory. This is one of the more recent ones that I recall. I remember an older one in Gramercy which contaminated some people’s apartments with asbestos and killed two workers. New York, on the infrastructure cutting edge during the industrial age, now seems to posses a patchwork of decaying systems which may fail spectacularly at any time. Yet steam is still mostly just chugging along, you don’t hear about it until something goes wrong, people don’t tend to complain about the prices or anything since all the customers are commercial, entire buildings rather than individuals paying a bill.

When it’s wet, big orange and white plastic stacks come out over the steam manholes, water hitting the hot pipes turns to vapor and has to vent. And that can be beautiful. There’s no doubt that the steam in the city has a very noir movie feel. At night if you are where there are steam vents it can seem like the small clouds coming from ground level and the tops of buildings are setting the scene for New York, to play the part of New York in a film. It’s good to step off a curb in your heels and get in a cab at these moments, or pull your hat down over your face and your coat tighter, so you can be an extra passing through the narrative. Leave your small trace in the vaporous night and disappear.